Subscribe to join thousands of other ecommerce experts

Every Account Manager understands the importance of Google Shopping title optimisation. But turn to Google for instructions, and you’ll find dozens of articles usually offering the same, limited set of general advice:

Common tips for Google Shopping title optimisation:

- Avoid short or vague titles

- Include the brand in the first position

- Include all relevant product infos

- Add differentiating features like colour

- Incorporate your best keywords

Infographics abound, all showing a standard set of templates for a standard set of example consumer verticals. Variations are scarce (unless you count the recommended number of characters, which is one thing no-one seems to agree on). It’s still worth mentioning that even if you make sure to follow these rules, Google can still alter your product titles.

With such concrete rules being handed down from one Account Manager to the next, it got us wondering: does Google follow these recommendations when it displays titles for Google Shopping? And what effect does changing titles have – in real numbers?

To answer the first question, we attempted to crack the code of Google’s own Shopping titles using statistical and linguistic analysis. This post details those results. In my next post, I’ll reveal some common differences we found between catalog and Google Shopping titles, and present the results and measures of statistical significance for a series of A/B title optimisation tests.

Table of Contents

Cracking the code of Google’s own Shopping titles: the setup

For any of our clients’ products eligible to serve in Google Shopping, there will be a Google Shopping title displayed for all merchants selling that product. Thus, we gathered the Google Shopping titles corresponding to our clients’ product titles (which we’ll call catalog titles), and set out to answer questions like:

- How often do Google Shopping product titles change?

- What is the ideal Google Shopping title length?

- Which words do Google titles add, remove, or keep, from catalog titles?

- Does Google ‘prefer’ specific punctuation and case patterns for product titles?

- Does Google always include a brand in Shopping titles? And is first position really best?

- Are categories important in Google Shopping product titles?

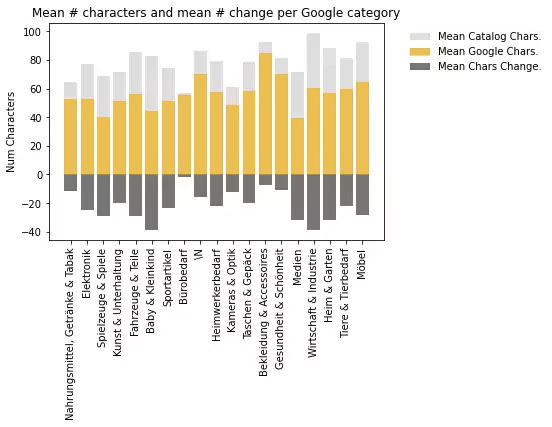

Since title recommendations often differ per vertical and product type, we performed our analyses over the whole catalog, and per Google category. We used the root level category, as this best corresponds to the well-known title templates available per product type.

How often do Google Shopping titles change?

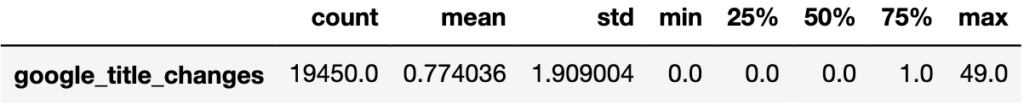

Our experiment data ranged over 30 days, during which time none of our clients changed their titles. The corresponding Google titles also changed less than once, on average, but the maximum number of changes was a whopping 49! So what can we learn from those changes? Let’s find out.

What is the optimal Google Shopping title length?

Probably the most frequently-recommended title length for Google Shopping title optimisation is 70 characters, as this fits on most mobile device screens. Sure enough, the Google titles we saw averaged 65 characters, which was an average increase or decrease of about 20 characters from the catalog titles, depending on their original length.

However, if you start short, you may still end up short: one client, whose titles averaged 35 characters long, ended up with Google titles of only around 47 characters. On the other hand, some Google titles broke their own rules, coming in at over 200 characters long!

Which words do Google titles add, remove, or keep, from catalog titles?

Looking at the individual words in the catalog versus Google titles, we were surprised to see only about a 50% word overlap.

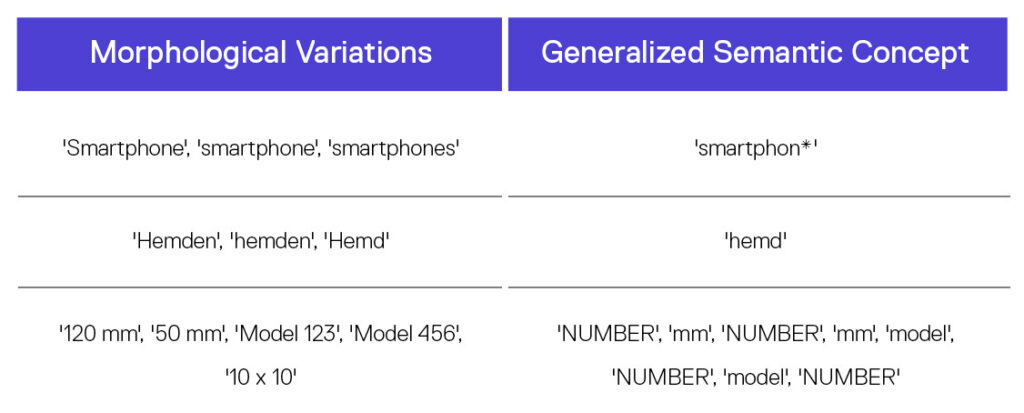

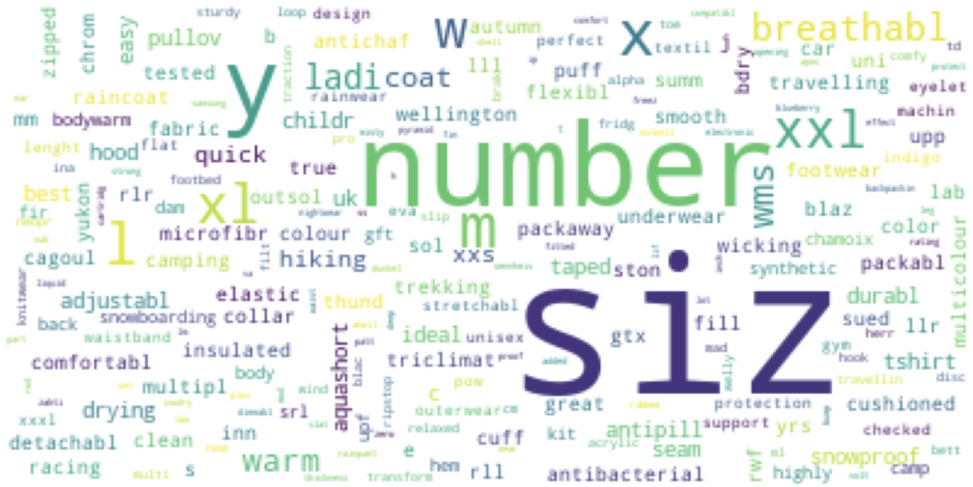

To investigate this, we processed all words via case normalisation (converting all to lowercase), tokenisation (slicing titles into individual words) and stemming (algorithmically slicing common suffixes from the word-end). This allowed us to concentrate on the title semantics, rather than morphological variations. For the same reason, we also replaced numeric tokens – which could correspond to sizes, dimensions, parts of product names, and so on – with the string ‘NUMBER’.

Token stems which appeared only in the Google titles were considered ‘added’, stems which appeared only in the catalog titles were considered ‘removed’, and stems appearing in both, ‘remained’. This is a little misleading – we do not believe Google starts with a catalog title and then adds and removes words to create something new – but we found the terminology useful.

Furthermore, when we say ‘most added’, we mean the set of stems which were most often ‘added’, minus the set which were most often ‘removed’ or ‘retained’. ‘Most removed’ is defined similarly.

The most added stems were clearly derived from colours and also included ‘NUMBER’. For one clothing retailer, stems for ‘women’, ‘men’, ‘girls’, ‘boys’ and the suffix ‘size {x}’ appeared often in the Google titles. And when the retailer name was itself a brand, such as ‘Cool Toys GmbH’ (not a real client), those name stems were also among the most-added.

What’s interesting about all of these terms (excluding retailer name) is that they were not present in the client feeds, such as in the custom attributes columns. So where did this information come from?

It is likely that Google has a knowledge base of products and their attributes, which it has crawled from e-commerce sites and manufacturer catalogues [1]. But based on our experience in natural language processing, the titles don’t feel like they were built using natural language generation (NLG) techniques applied to such a knowledge base: firstly, they are too human, and secondly, we are yet to see good examples of NLG used for product titles outside of research labs.

Our best guess is that for each product, one title is selected from the merchant feeds of retailers selling that product, and then automatically tweaked. It would make sense if the title chosen for tweaking was picked based on performance metrics: those which maximise clicks and cost-per-click, while also having decent conversion rates. That way Google makes its money, and shoppers find the items they want to buy.

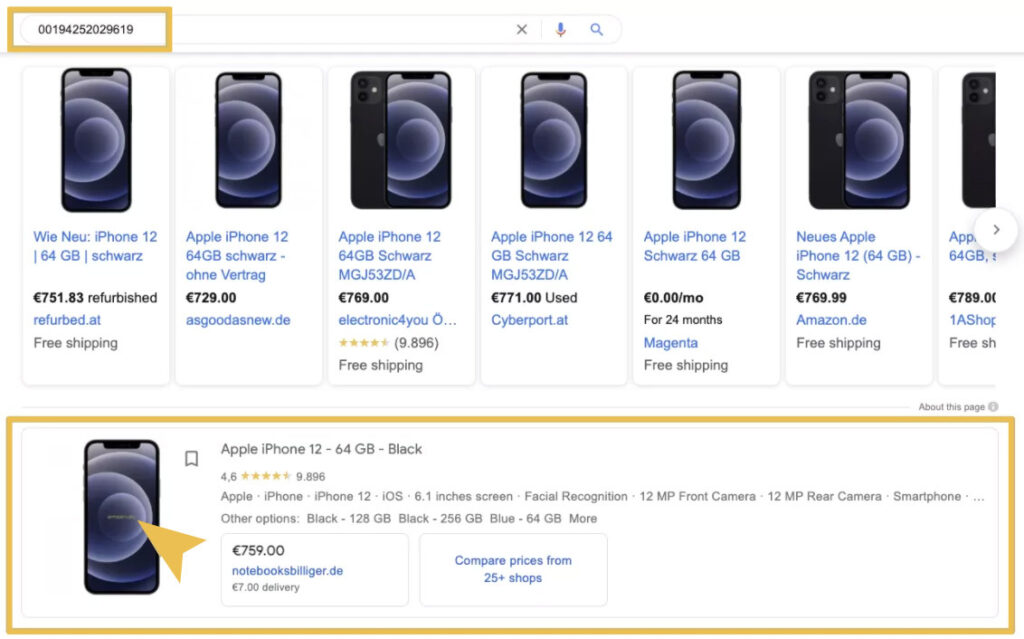

So if you are an e-commerce Account Manager, you might want to look up your GTINs in the Google Shopping tab. There you could find some ideas to try out for your Google Shopping title optimisation:

Now, back to our token-changes exploration. Surprisingly, the most ‘removed’ stems were often perfectly valid attributes, such as technical details. This seems due to the Google titles being generally shorter.

For example, one client had long titles which included the product categories, which were missing in the corresponding Google titles. Thus, their most ‘removed’ stem was ‘smartphon’. This sounds detrimental, but doesn’t have to be: After all, if the product name is ‘Samsung Galaxy XYZ’, then ‘smartphone’ is not particularly useful. Other ‘removed’ stems, which seem more intuitive, included various misspellings.

The most retained stems were customer- and vertical-specific: simply product descriptors which happened not to end up in a most-added or -removed list. And Google titles featured a higher percentage of numeric characters, implying that these were more likely than alphabetical characters to be added or retained.

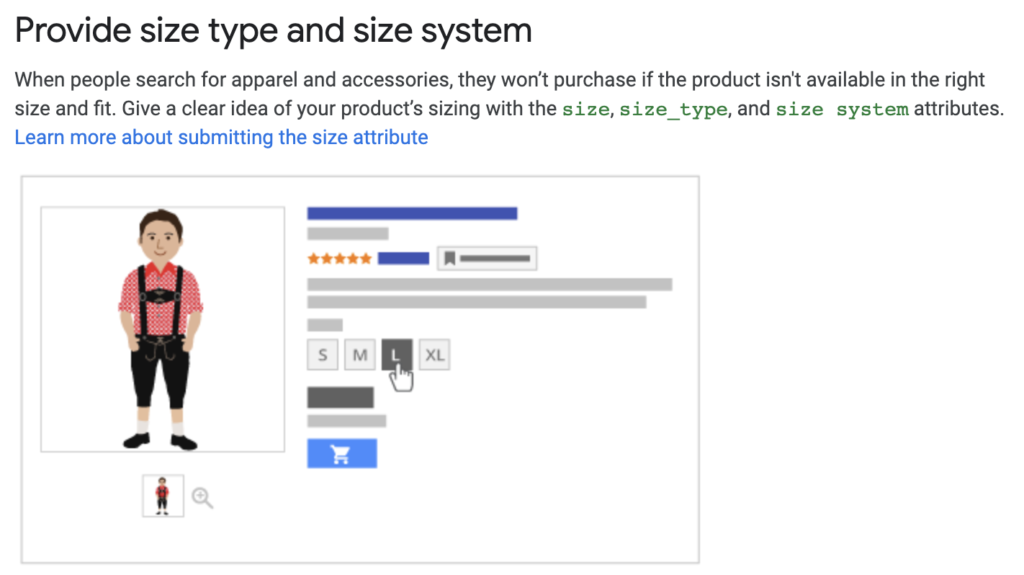

Does Google ‘prefer’ specific punctuation and case patterns for product titles?

It’s generally recommended to avoid too much punctuation, lest your titles look spammy. But it can be used nicely, to highlight product attributes:

iPhone 12 | 64 GB | black

We half hoped the Google titles would show consistent punctuation patterns, thus revealing new structural best practices. In reality, the percentage of punctuation characters was fairly consistent across both title types, although Google did have a couple of crazy titles with up to 28 of them! And while the characters used did change, as in the below example, this was not consistent between clients.

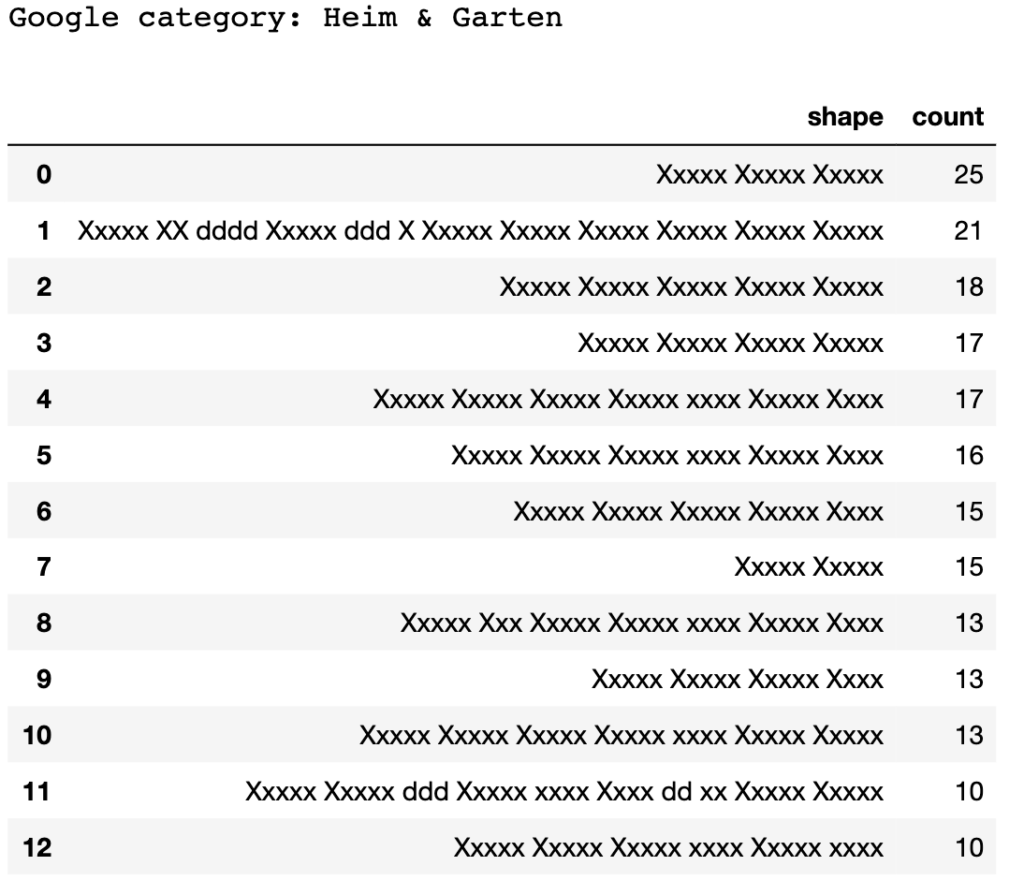

Still on the hunt for generalisable structural patterns, we also examined title shapes: we replaced upper- and lower-case characters with ‘X’ and ‘x’, digits with ‘d’, and truncated any sequence of these to a maximum of four (since individual word length is not relevant to overall structure). The catalog titles exhibited a tendency towards title-casing, which the Google titles preserved.

Given this apparent preference for sentence case titles, how did Google handle brands whose official orthography included non-conventional capitalisation? Does ‘LEGO’ become ‘Lego’ and ‘brother’, ‘Brother’? Both! Google was wildly inconsistent here: for one month and one title, the brand could be represented in many different ways, even if the rest of the title remained unchanged. Similarly, if the brand featured special characters, such as trademark symbols or special accents, their presence in Google titles varied considerably).

Even when a brand with non-sentence-case capitalisation was represented correctly in the catalog titles, it often wound up wrong in the Google titles, and not necessarily due to strict adherence to sentence casing.

Does Google always include a brand in Shopping titles? And is first position really best?

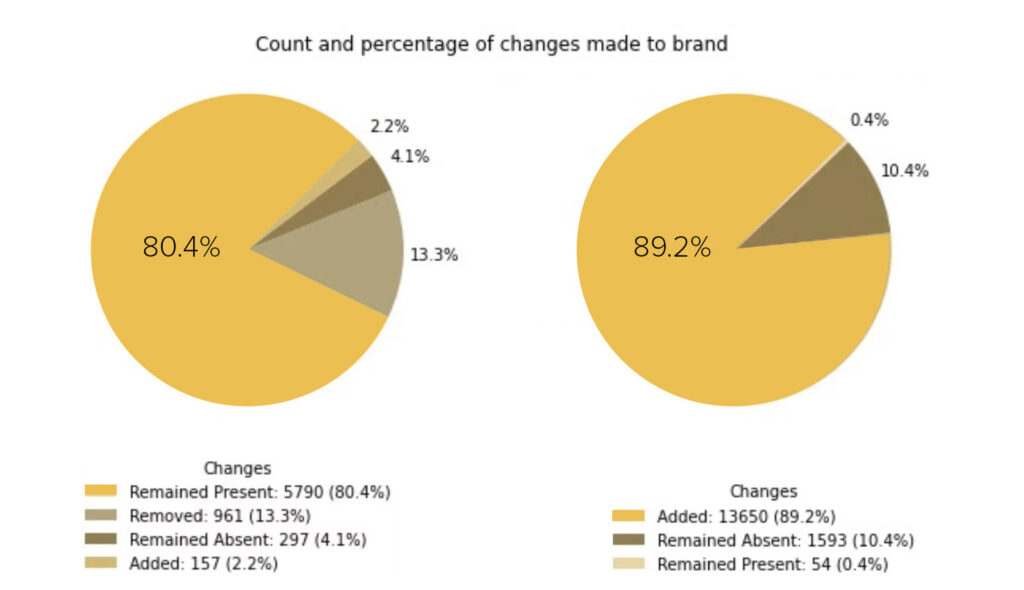

Including the brand, and placing it early in the title, are two of the most common rules in the Google Shopping title optimisation playbook. We built a special brand matcher, robust to the many inconsistencies with which brands were represented, to test this.

Most catalog titles included the brand, so there was no change here. However two interesting cases stuck out: one retailer had only a few brands – it’s own name plus a couple more – and brand was rarely present in their titles. The corresponding Google titles included the brand – but only when it was the retailer name.

Another retailer, being a generalist, had many brands, which were actually ‘removed’ from the Google titles. They included many media publishers, such as film and video game studios, perhaps because those film and game names are a stronger selling point than the studio itself.

What about brand position? Considering only cases where the brand was present in both titles, the brand started about one word later in the Google titles. And when considering only cases where the brand was present in both, and there was a change, the Google title brands came later still! In fact the only intuitive result we found was that this pushback was less pronounced in the category ‘clothing and accessories’, where brands are a strong drawcard.

Are categories important in Google Shopping product titles?

A ‘main category’, defined by a retailer, or a ‘Google category’, taken from Google’s product taxonomy, can be a simple, general means to describe a product. However, we found Google titles contained fewer category words than catalog titles did, although these were ‘added’ if catalog titles were short.

We also saw that Google titles always contained more main category terms than Google category terms. Presumably this is because Google ‘understands’[1] its own categories and can access them anyway via the merchant centre feed, meaning it can still serve this product if it detects a purchase intent for that category, even if that category is not in the title.

Lessons learned

In this first part of our extensive title optimisation investigation, we wanted to learn whether Google follows known ‘best-practices’ when it displays titles for Google Shopping. To some extent, it seems so: titles were around 70 characters long and included specific product details like numeric tokens, sizes, colours, and the retailer name. Sentence casing was common. Thus, if you’re a PPC manager following these practices, this is a good start. However, we also found that the brand was often shifted away from first position, and categories were often not present, and even ‘removed’ from Google titles. Thus, it’s clear that the well-known ‘best practices’ aren’t everything. So what should you do instead? Experiment.

If you are interested in further ways to optimise your Google Shopping campaigns, you can check our article on optimising your campaigns with profitability data. Have a great day!

[1] We intuit that Google may build up a database of product information, similar to its Knowledge Graph, which is used to answer all web queries: https://support.google.com/knowledgepanel/answer/9787176?hl=en. Amazon also uses machine learning to build and update a knowledge graph based on it’s own pages’ product listings and the open web: https://www.aboutamazon.com/news/innovation-at-amazon/making-search-easier